I had just sat down in a movie theatre when I opened Instagram and saw that Bob Weir, cofounder of the Grateful Dead, had died at 78. While 78 isn’t an unusual age to die at, I was still shocked. Weir was the youngest member of the band, and always the most active. I had heard the rumours that swirling around as fall came and went without any tour announcements. I had seen videos from the Grateful Dead’s 60th anniversary shows at Golden Gate Park in San Francisco where he seemed to be struggling, but I dismissed it as an off night. I didn’t take any of it seriously. The Dead have been a constant in my life since 2020, which is not nearly as long as most Deadheads, but considering I was 13 at the time, I think it still shows commitment. Every year since 2021, I came to expect some form of live performance, which I would follow through recordings and illegally broadcast livestreams shared to those of us unwilling to pay for tickets. I had never seen him, or any other member of the Dead, in concert, but I always carried around the assumption that I would. That one day, he would announce a show in Toronto, and I would finally get to see one of my favourite performers live. That day never came, and now it never will.

I’m sure someone in the theatre turned to look at me when I let out an audible “fuck” as soon as I read the words “profound sadness” under a picture of Weir from his official Instagram account. I didn’t need to read the rest to know what it meant. It’s the burden you live with when you love the music of anyone over the age of 70: that one day you’ll be scrolling through social media and discover that someone whose art changed your life is gone. It’s an undignified way to find out, to see something so serious in a sea of shitposts and other nonsense. I felt the strong urge to leave; to go home, put my headphones on, and spend the rest of my night in bed listening to his music. Before I knew it, the film started and I decided to stay. I don’t know why. The ticket was free. The only money I would be losing would be the TTC fare that got me there.

Some two-odd hours later, the movie was over, and I hadn’t really paid attention. I put my headphones on, and I queued up “Black-Throated Wind” from the Dead’s performance in Veneta, Oregon on August 27th, 1972. It’s one of my favourite songs Weir had his hand in, co-written with his frequent songwriting partner John Perry Barlow. It’s an incredibly vulnerable song about losing love and realizing later that it’s your fault. “You’ve done better by me then I’ve done by you,” Weir sings before the song concludes with him repeating the refrain: “I’m drowning in you.” It ended just as I reached the subway station. I followed it with “Cassidy,” a version from the Dead’s acoustic live record Reckoning. I didn’t think about how fitting that song’s refrain was to the situation. “Faring thee well now/Let your life proceed by its own designs/Nothing to tell now/Let the words be yours, I’m done with mine.” I spent the rest of the night listening to that record, among others.

I emphasize the live element because that’s the appeal of the Dead for most fans, including me. I have a great deal of love for the studio recordings, but the band came to life in concert. As a teenager living in a rural area in the midst of a global pandemic, live music was not something I experienced at all. There was no ‘scene’ before a pandemic interrupted whatever concerts were happening in Northumberland County, Ontario, and there certainly wasn’t when in-person events started again. So, I lived vicariously through the Dead. I listened to hundreds of live performances from every era of the band, from early psychedelic bar-blues in the mid ‘60s to the heroin fog of the mid ‘90s. I found something to love about all of it. I read countless tour diaries from fans who, unlike me, actually had a chance to follow the Dead around the country and got by on funds from selling trinkets in the parking lot outside the venue the night of the show. I knew that one day, when I lived somewhere else, or when I had the means to travel, I would finally get a chance to experience it for myself. Of course, the scene that followed the band in the ‘80s and ‘90s had mostly split after lead guitarist and singer Jerry Garcia died, and most shows were too expensive to get into by selling grilled cheese now, but I wasn’t thinking about that. Even a single show would have satisfied my desires. I just wanted to see the Dead (or some form of them) once. But I didn’t, and now I won’t.

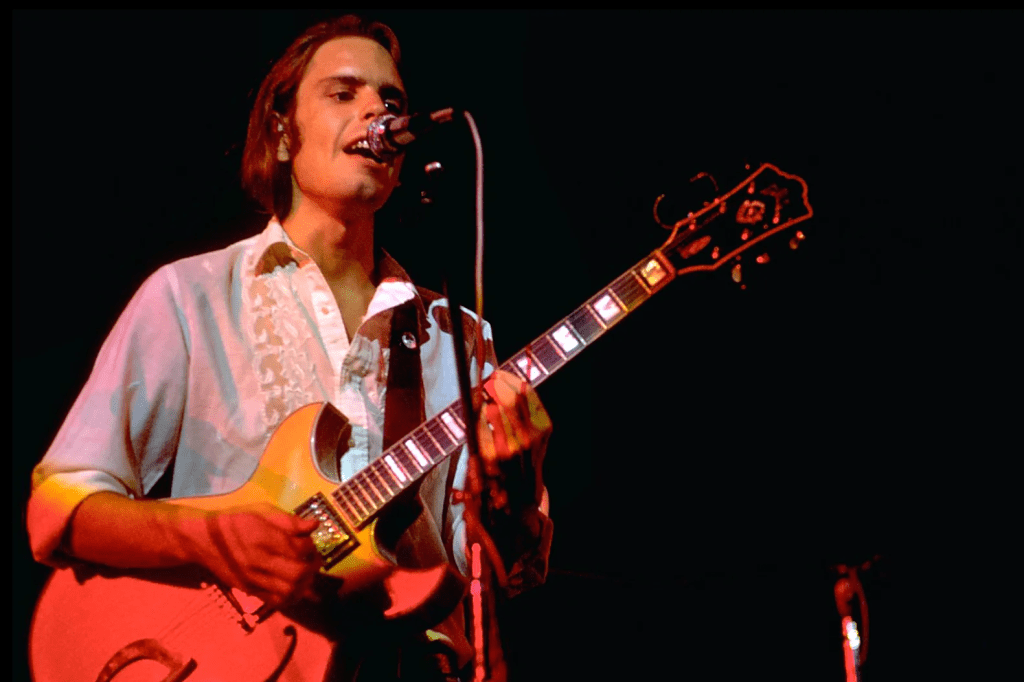

Most of what can be said about Weir has already been said in the sea of eulogies that have come out since he died. He was an incredibly unique rhythm guitarist, influenced heavily by jazz pianists like McCoy Tyner, leading to a style based on fragmentary chords and strange inversions. It’s not a style that would work for most bands, but it worked for the Dead. So did Weir’s longstanding songwriting partnership with Barlow, where he produced most of his best work. I’m particularly interested in Weir’s late-career renaissance, spurred by the Dead’s brief reunion in 2015 for a series of final shows. The band’s commercial power had been largely erased after Garcia’s death in 1995, but 20 years later, under Weir’s leadership, they could fill stadiums again. Within a year, he had released his first solo album since 1978 — 2016’s Blue Mountain — and formed the Dead’s biggest, and final post-Garcia incarnation: Dead & Company, featuring John Mayer. Blue Mountain is, in my opinion, one of the strongest late-career albums of all time, and certainly Weir’s strongest solo album. His voice aged incredibly well and is perfectly suited to the material. Sonically, it’s essentially an indie-folk album. Weir’s voice is drenched in reverb and accompanied by gentle instrumentation with beds of effect-laden guitars. Dead & Company, with the added name recognition brought in by former teen idol Mayer, toured regularly until 2023, and then performed several residencies at the Sphere in Las Vegas. Their shows in San Francisco’s Golden Gate Park in 2025 were Weir’s last. Plenty of legacy artists fill stadiums, though. Dead & Co. were special because they actually approached music in new ways. They weren’t a group of old men going through the motions, and they didn’t pad the band with younger hired guns for the sole purpose of replacing dead members. A band willing to actually engage with their music 60 years into their career is incredibly rare. Wildcard John Mayer is a choice that really shouldn’t have worked. Most people can acknowledge that he’s a great guitarist, but not one whose style fit the music the Dead played. I can’t imagine anyone thought of him as a replacement for Jerry Garcia before it actually happened, yet despite that, he excelled. His guitar playing, while clearly taking inspiration from Garcia, was something completely new to the Dead. The songs he sang were mostly songs that suited his vocal tone, with Weir taking on more of Garcia’s songs as a result. The setlist of a Dead & Company show might’ve resembled that of your average Grateful Dead show, sure, but the nature of the music—the free-flowing jams that could last 40-plus minutes—meant that it was significantly different too.

I’ve spent a lot of time trying to justify the importance of Weir’s legacy, but the real point of all of this was to reinforce one specific truth: I loved him. He was one of my favourite musicians ever. I’ve spent hours poring over live footage to pick out specific chord voicings. I’ve stayed up late on school nights watching dozens of Dead & Company shows via pirated livestreams. I’ve probably heard even his worst songs hundreds of times. There was a point in my life where I could safely say that my fandom for the Dead, and Weir by extension, was one of my defining personality traits. Bob Weir defined what I thought a rockstar should be, what a rhythm guitarist should be, and what a songwriter should be. He was great, and now he’s gone.

Leave a comment