In the past few years, I’ve been noticing a rising trend on social media centering on reviving the Riot Grrrl subculture. Examples of this range from the prevalence of viral audios which span new Riot Grrl releases such as “Wet” by Dazey and the Scouts to classics like “Deceptacon” by Le Tigre. Do teenage girls yearn for the nostalgic vibes of ‘90s Riot Grrrl?

Riot Grrrl began as a subgenre of underground punk that was established in the early 1990s. The specific name “Riot Grrrl” was coined in Olympia, Washington, where women involved in the local scene held a meeting to address the sexism they experienced in punk communities. Centering around feminist issues and supporting women’s liberation in a predominantly male punk scene allowed zine culture to prosper in Riot Grrrl, creating a safe space for women to spread information and address issues within local communities.

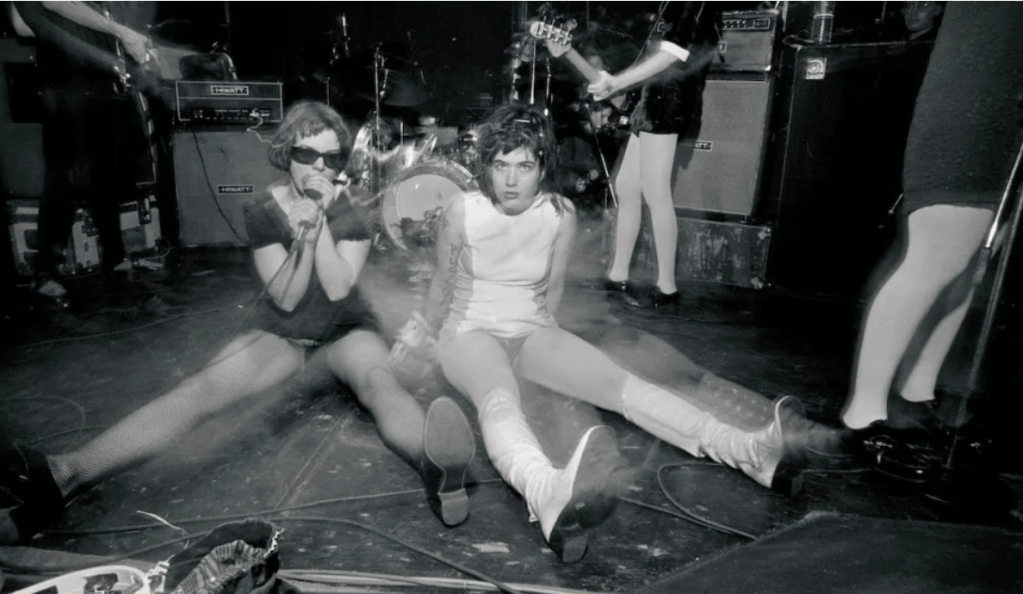

In terms of music, instead of being united by one distinct sound, Riot Grrrl encompasses any sort of punk, hardcore, and rock which holds an underlying theme of feminine rage. Early Riot Grrrl bands like Bikini Kill, Bratmobile, 7 Year Bitch, and Sleater-Kinney interpret this rage in a vast range of melodies and styles, opening Riot Grrrl to many different musical subgenres. An abundance of iconic symbolism and aesthetics emerged in this era, the most well-known being the grungy ‘kinderwhore’ fashion aesthetic sported by Hole’s frontwoman, Courtney Love. A mini white-lace babydoll dress, layered with a dark flannel and a bold red lip would end up being the main attire associated with Riot Grrrl’s fashion scene.

However, the Riot Grrrl scene began to decline from the mid-to-late 1990s. Instead of being a movement meant to include women that were excluded from male-dominated punk and rock scenes, Riot Grrrl actively excluded women of colour and transgender women. It was built on white feminism, rather than the feminism that speaks about race, disability, and sexuality issues which affect all women. Riot Grrrl was essentially a white supremacist space, just like how many alt-right punk communities operated in going against what punk values truly are. Riot Grrrl needed to go, for the sake of keeping alternative spaces safe and inclusive.

This bitter end to such a moment raises the question: why is Tiktok trying to revive Riot Grrrl? If Riot Grrl ended so terribly, is there any way modern punk bands can transform this movement into something inclusive? New bands like Cheap Perfume, Mommy Long Legs, and Dazey and the Scouts claim to be part of a modern reinvention of the Riot Grrrl movement. It seems genuine for the most part, but I still feel fairly skeptical. Don’t get me wrong – I love what modern Riot Grrl is trying to emulate. But at the same time, it can be hard when you don’t know who exactly is there to effectively reshape the genre, or to fall back into reinforcing the same transphobic and white supremacist ideals. Luckily, I was able to take part in listening and understanding the local Riot Grrrl scene in Toronto – made by queer women and women of colour – to give my own interpretation.

“BWBB,” (shorthand for “Boys Will Be Boys”) by Softcult was the very first song that shifted my opinion positively towards Riot Grrrl. I was introduced to this song at the very first concert in this genre that I attended. Before performing this song, Mercedes Arn-Horn, the lead singer, dedicated a small speech to Sarah Everard. Sarah Everard was an English marketing executive who was raped and murdered by a police officer after walking home alone at night. This tragic headline snowballed into a larger social movement to address rape culture and the abuse of power by men in positions of authority. While “BWBB” technically does not fall within the broad categorization of a Riot Grrrl song, it still remains unapologetically feminist, which is the overarching theme of Riot Grrrl as a movement. Softcult defines their sound as “riotgaze,” taking Riot Grrrl’s political messages and incorporating them into shoegaze. “BWBB” perfectly exemplifies how a song can act as a force of radicalization, even at a young age. The song speaks to something which, sadly, every teenage girl inevitably fears. We are taught to tolerate men’s behaviour to the point where instead of teaching men consent, we fear walking home alone at night. This song explicitly describes these feelings within the lyrics, which is comforting for many to hear out loud.

I later fell into a rabbit hole of radical feminist politics and punk music, sparking my new profound interest in Riot Grrrl. Sometime last summer, I went to see Kittie, a nu-metal band that is also somewhat associated with Riot Grrrl, due to their early releases centering around themes of misogyny. I was initially unfamiliar with the openers before the concert, yet I found myself gravitating towards Dear Evangeline. Dear Evangeline, a hardcore band from Brampton, blew me away with their outspoken violent energy. My favourite song of theirs, “BITCH,” from their self-titled EP, channels pure feminine rage. The song opens up with a spoken intro, “I like to scream, I like to holler, I like to break things, I like to yell. I like to get my anger out,” painting themes of destruction and anger. There is nothing more Riot Grrrl than being loud and outspoken and calling men bitches. “BITCH” by Dear Evangeline accomplishes all these things with an intense live sound and heavy attitude on stage.

Duchess is another talented hardcore band that I was introduced to through a live show. While Duchess officially released their debut single “Treat the Symptom” in October, they have been fairly active at local shows this year. I went to one of them, unfamiliar with any of the bands performing that night. Duchess specifically stood out to me because of their flashy attire. The aesthetic glamour of their lead singer, Kate Congress, takes inspiration from a Vivienne Westwood-esque blend of 1970s UK punk fashion and 18th century historical fashion, with aspects of bold patterns, combat boots, over-the-top jewelry, and a dramatic headpiece. While not exclusively seen as a fashion subculture, Riot Grrrl is all about standing out and refusing to be silenced, which Duchess achieves effortlessly from their fashion alone. Aside from the visuals, “Treat the Symptom” is a very dramatic song, which successfully ties lyrical elements of Riot Grrrl and the genre style of hardcore punk.

It is important to understand Riot Grrrl’s history and its complications before we glorify the movement as the pinnacle of feminist punk. Yes, Riot Grrrl helped pave the way for many female artists, but it was built on an extremely white-dominated space. Reviving this movement correctly means supporting women of colour and transgender women in Riot Grrrl bands, zines, and alternative communities. Tiktok’s revival of Riot Grrrl is still somewhat pushing the same few bands which participated in transphobic behaviour and the exclusion of racialized groups. However, this doesn’t truly reflect how the Riot Grrrl movement is being revitalized. Toronto’s local Riot Grrrl scene is doing a fantastic job including and supporting all women in the space– without Softcult’s “BWBB” and my continuous journey exploring Riot Grrrl through live shows, I would have not wanted to see Riot Grrrl to become popular again, fearing that it might fall down an exclusionary path once again. Fortunately for Toronto’s punk scene, Riot Grrrl has been beautifully and expertly reshaped to fit our city’s diverse communities.

Leave a comment