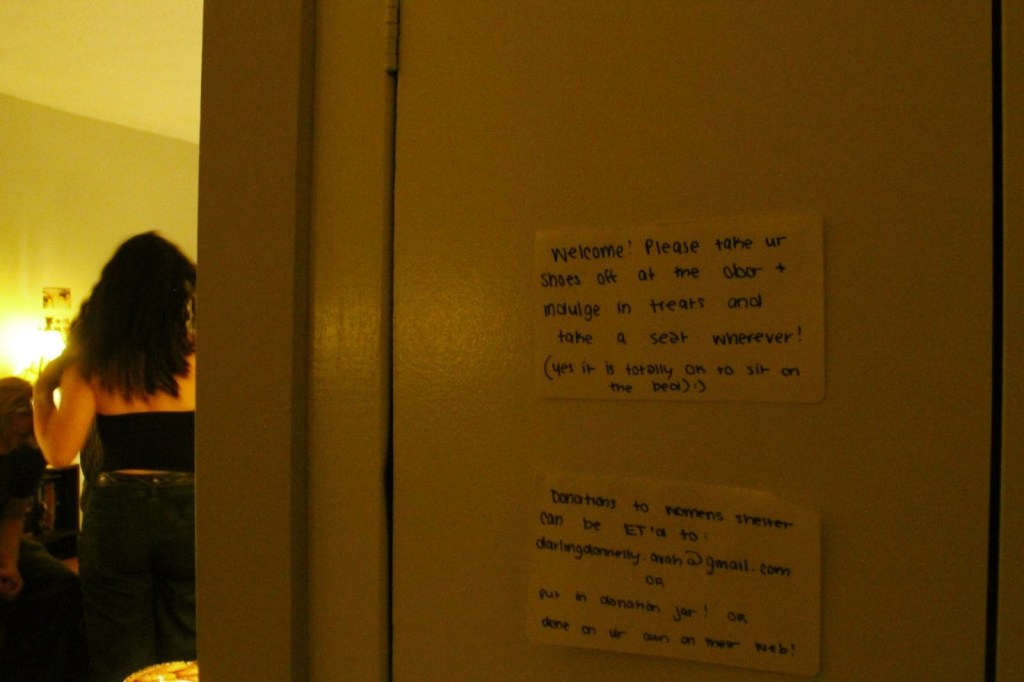

Four weeks ago, a friend of mine sent me a post from an Instagram account by the name of @kitchensinktoronto announcing what they dubbed a “new teensy apartment venue.” I knew nothing about this account beyond what I could gather from that singular post: it was independently organized, the vibes were cozy, and the event would be collecting funds to donate, in full, to a local charity. In pondering on who could be behind it all, I was hit with a sudden realization: It’s gotta be Marzieh. By that I mean Marzieh Darling-Donnelly of renowned Hamilton band Superstar Crush, the previous host of the Hamilton/Toronto third space The Coffeehouse, and someone I have admired for many years. I knew I had to come check it out.

Just two days later, Kitchen Sink’s debut show took place. Upon arrival, I was brought up to the apartment by Darling-Donnelly herself, catching up with her as we made it up the stairs. An already sizable pile of shoes greeted me as we entered, and I was told the bathtub had been turned into a rest stop for guests to leave their bags. The venue was, in fact, teensy. I said my hello’s to those already there and took a look around, stopping at the snack table for a pecan tart and a cup of tea. The floorboards grew less and less visible with each new face that arrived. I mingled for a little while longer until Darling-Donnelly took the floor to formally welcome us all into her space and introduce the two musical acts, Lila Wright and Sam Hansell. Both Wright of Meteor Heist and Hansell of Superstar Crush actively play with their respective bands while also having solo careers of their own. We were in for some special sets.

First up was Wright, who graciously took the makeshift stage—a wooden chair in the centre of the kitchen’s tiles. After introducing herself, she began to play, the once chattery room now pin-drop silent as the crowd shifted their focus to the singer and her guitar. It was my first time hearing her play alone, and immediately, I was captivated. Wright’s vocals were entrancing. Beautifully soft yet palpably raw, suddenly transposing into powerful cries, which melted together with the strumming of her guitar. Multiple times throughout her set, I found myself idle, my hands on my lap rather than my camera. This was in part as to not interrupt with the sound of the shutter, but more significantly to take in each line that flowed so purposefully into the air. Acoustic had never sounded so good.

Wright’s set consisted of both originals and a few curated covers, with brief verbal segues from the singer between each one. It was during these pauses that the intimate nature of the venue really came to focus. You could see as Wright scanned the room, shifting her gaze from face to face as she shared the detailed backstories of original songs and emotional connections to covers. It’s not every day that as an audience member, you’re given the chance to know an artist’s thought processes and narratives behind a song immediately before it is played, making for a performance that was not only lovely but felt deeply personal and real.

Hansell’s set was a slight change of pace from the mostly soft melodies of the last. His original songs were dynamic, moving, and full of soul, with lasting and clever lyricism that garnered chuckles here and there from the crowd. As I sat atop the kitchen garbage can, I saw each face in the room glued to the stage, gratefully gazing at the musician and his guitar. Hansell is a magnetic performer, and from so close up you can really see the passion he puts into each facet of his work.

The small-scale setting once again allowed for some memorable moments. At the beginning of his set, Hansell went back and forth between his guitar and Wright’s, tuning and strumming until everything sounded right, all while making quips and conversation along the way. These continued on during pauses between songs, as he turned the fan on and off to alleviate the heat. Here, I truly felt a sense of togetherness as I sat shoulder to shoulder with the people around me and less than a metre from the musical act. By the end, I only wished the experience lasted longer—though I was glad the fan would be staying on for good.

After a gracious closing speech from Darling-Donnelly, the guests trickled out of the apartment, making room for our interview to be conducted while Wright, Hansell and co. indulged in some Silksong. Just outside her door, we took the interview, conversation and laughter and sounds of life just barely muffled by the drywall behind me. My first question (which I’m sure I shared with the majority of people who saw that first post on Instagram) was, What even is Kitchen Sink? As it turned out, even Darling-Donnelly herself was not entirely sure.

“I guess I’m a musician,” she humbly began. “I was taught by my parents, who always hosted things like this, that anything that you do in your life should be directly related, in some capacity, to the betterment of the world. I think it’s supposed to be a reconciliation of the incredible musicians I know who should have their music heard. Local artists contributing to a local or international cause in my apartment.”

This air of ambivalence was somewhat fitting, as the idea only came to her about a week prior from none other than her mother, who had taken one look at the space and told her, “That kitchen looks like a stage.” Given the size of the place, it initially seemed absurd, but the idea stuck as she explored it further. “It’d be cool to have musicians who, maybe, they’re nervous to play in front of more than 25 people. Good. The space can only fit 25 people.” She continues, “It’s great because I get to gather all these different people from different parts of my life and they get to come into a common space and maybe create some difference.”

At the same time, hosting is no new feat for Darling-Donnelly. For years, she and her friends and family organized The Coffeehouse, a third space that led meaningful discussions surrounding philosophy and literature followed by live music from local bands, with drinks and snacks aplenty to enjoy. The majority of the events took place in her own family home in Hamilton, and it was at one of these shows during the summer of ‘23 that I first experienced her innate hospitality, where she heated up a whole frozen pizza without hesitation for my friend who told her he was hungry. This memory stands as a testament to her drive to foster connection within the community that she’s built over the years, and the genuine love and trust she has in that community despite her awareness of the risks that come with inviting strangers into your home. “I guess I don’t think about it that much. When people come into [my] space, I’m like, ‘Oh, well, this is your space too.’ It doesn’t even really feel like mine.”

Darling-Donnelly credits this mindset to her unique upbringing: being raised Baháʼí, with two parents in the entertainment industry, and growing up in a house that always had people in it. She recounts the similarly-structured gatherings her parents would often host throughout her childhood. There, she came to appreciate the power of human connection in creating positive change. This notion was reflected abundantly in The Coffeehouse and once again with Kitchen Sink. As per the thesis statement of the Baháʼí faith (in her own words), “Your purpose in life is to better your community, actively contribute, and even sacrifice yourself in whatever capacity that you can to contribute—though I don’t really feel like this is any sort of self-sacrifice.”

These values manifest equally in the charity portion of the event, where 100% of the proceeds went to Sistering on Bloor, a drop-in centre for at-risk women and gender diverse people in need of support. While not enforced, guests were encouraged to contribute to the cause in any shape or form they could. Darling-Donnelly breaks it down: “Kitchen Sink is my attempt to reconcile music, the amount of time I’m spending doing music, the amount of incredibly talented people that I know, and the issues that I know this locality has.” She highlights homelessness as one that she found especially prevalent in Toronto, which is why Sistering was her first choice of organizations to support. Being just blocks away from her apartment, the impact remained local, though Darling-Donnelly’s sights are set high—Toronto was at the forefront of her mind, but the city is just the beginning. “I’m going to try to expand it to international funds and international issues. I think that charity can be discounted as a way to make change, but when it’s made through community, then you’re creating community, and you’re creating some sort of fiscal contribution.”

Kitchen Sink’s debut show raised over $100 for Sistering, so clearly Darling-Donnelly’s doing something right. After our interview, we moved back inside to find Wright, Hansell, and the others engaged in a hearty banter, the space now physically emptier but feeling no less full. I took my final photos, ate the other half of my pecan tart, and left down the fire escape with the group for an impromptu run to Taco Bell. There was truly something magical in the air—and it wasn’t just the Baja Blast.

In a post-Kitchen Sink world, Wright’s band Meteor Heist is working on another release for sometime around January, and in her solo career, she is in the process of writing a record of her own. She also has plans to form an all-female band and is currently looking for female artists and musicians to collaborate with. As for Hansell, he will be performing for the London music festival VENUExVENUE on November 7th with his solo band.

On the whole, Kitchen Sink’s future is bright, be it in the artists it will platform, the appetites it will fill with tarts and tea, or the positive impact that will no doubt be left on Toronto and the world at large. As a supporter and friend of Darling-Donnelly, I can’t wait to see where this project goes.

Q & A WITH LILA AND SAM

I’ve always been intrigued by artists that are in bands that pursue solo music ventures. How does playing solo compare to playing in a group?

L: In terms of songwriting, in Meteor Heist we’re very collaborative writers, so it’s pretty rare that a song will come in with less than two members of the band having worked on it before it’s brought to everyone and then everyone arranges it together. [It’s] so beautiful, but also can be challenging when you have a song you’re emotionally attached to and it doesn’t end up working for the band. Whereas when you’re writing for yourself, if you have a song that you like, you can play it. That can be really freeing, but it can also mean that you have to be a lot more self-critical. Both are really wonderful and serve a distinctive purpose. Performing is also vastly different. I can walk into a Meteor Heist set and turn off every part of my brain that’s not Meteor Heist and everything else becomes muscle memory. When you’re playing by yourself, it’s so much more intimate and personal and every part of your brain is firing.

S: If I could only be one for the rest of my life, I would love to play with the band. But especially after these months of touring and gear hauling, it’s a bit liberating to walk into a place with a guitar and nothing else. You can still be very spontaneous on stage with a band, and [with] some bands it almost seems like they can read each others’ minds and they can just pull shit out on the fly, but if you’re just playing by yourself, you don’t have to consult with anybody. You can really just change things up whenever—speed up here, slow down there, add another section… There were parts during that set where I forgot something or I did an impromptu intro, and that’s something that’s fun about playing solo.

Do you ever feel like your success is intrinsically linked to the band, or is it really not that deep?

L: There would be no way for me to remove my image from Meteor Heist, but I also would never want to because I’m so proud of the work that we do. I do feel very associated with that band even outside of musical endeavours. Whenever I have to write a bio for something else, the third line is always like, “and I’m in Meteor Heist!” It’s very much a part of my life, and I would never want to change that.

S: I’ve thought about it a little bit. Superstar Crush is more popular, for good reason because we’ve tried to make it more popular, and I think with a group, that’s what I want it to be. We’re kind of an accessible band, and I like that about us. Not to say my solo stuff is crazy alienating or anything. In terms of my identity being linked to the band, I like it a lot. And if people find my solo stuff through Superstar Crush, I’m happy for it. I like that it’s this little thing I can do on the side and I can be however strange with it as I want to be.

In what ways does the experience of playing for such an intimate show differ from that of playing on stage for a larger audience?

L: I probably feel more comfortable playing Meteor Heist shows and playing for bigger audiences. I’ve done the Meteor Heist set so many times that it feels a lot less stressful to me. But there is something about this that can also be a little bit more relaxing, because when you’re playing for a crowd of however many people, it kind of blends into one big glob of “the crowd,” which can be really scary if you feel like things aren’t going well. You can kind of project this image of animosity onto the nebulous blob of crowd; the crowd reacts however you decide they’re reacting. Whereas in a space like this, it’s so small that if you look up, you can see every single person’s face and you know exactly how everyone’s feeling. Luckily, this is a very kind space.

S: I definitely feel more comfortable in the larger band environment. I’ve done very few of these small, intimate acoustic shows. It was very nerve-wracking. Before the set, I had coffee shakes, I was kind of tweaking a little bit, breathing a little heavy. A lot of [the songs] I had never played before for an audience. I realized I kept my eyes closed for the vast majority of the performance, and that’s not something I do for Superstar Crush. That’s like, I’m really looking around, I’ve got my head on a swivel. I would love to get more comfortable with this.

FOR LILA: Is there something special about playing covers that draws you to continue playing them?

There’s two categories to covers that I like to play. Songs I wish I wrote—songs that, when I listen to [them], I’m like, “Oh my god, I just wish that I had these words come out of my brain,”—and covers that exist in this world completely outside of music that I could write, like two of the covers I played today, “Fire Truck” by Andy Schauf and “Officer Down” by NQ Arbuckle and Carolyn Mark. They all have themes that I really connect with but are never songs that I could write from my own perspective just because that’s just not a life that I live.

FOR SAM: How do you go about writing love songs that reference your own relationship versus ones in character?

I’m pulling from my own experiences for all the songs that are explicitly about Marzieh. For the character songs, which tend to be more on the pessimistic, negative side, those aren’t actually about Marzieh in any way. The inspiration is the conflict. I think conflict can drive a lot of really compelling songs. There’s a lot of, obviously, dysfunctional relationships in the world, and I think it is still possible to write about them while being in such a happy relationship. I hope people don’t think that things are awful behind the scenes or anything.

Leave a reply to SJP! Cancel reply